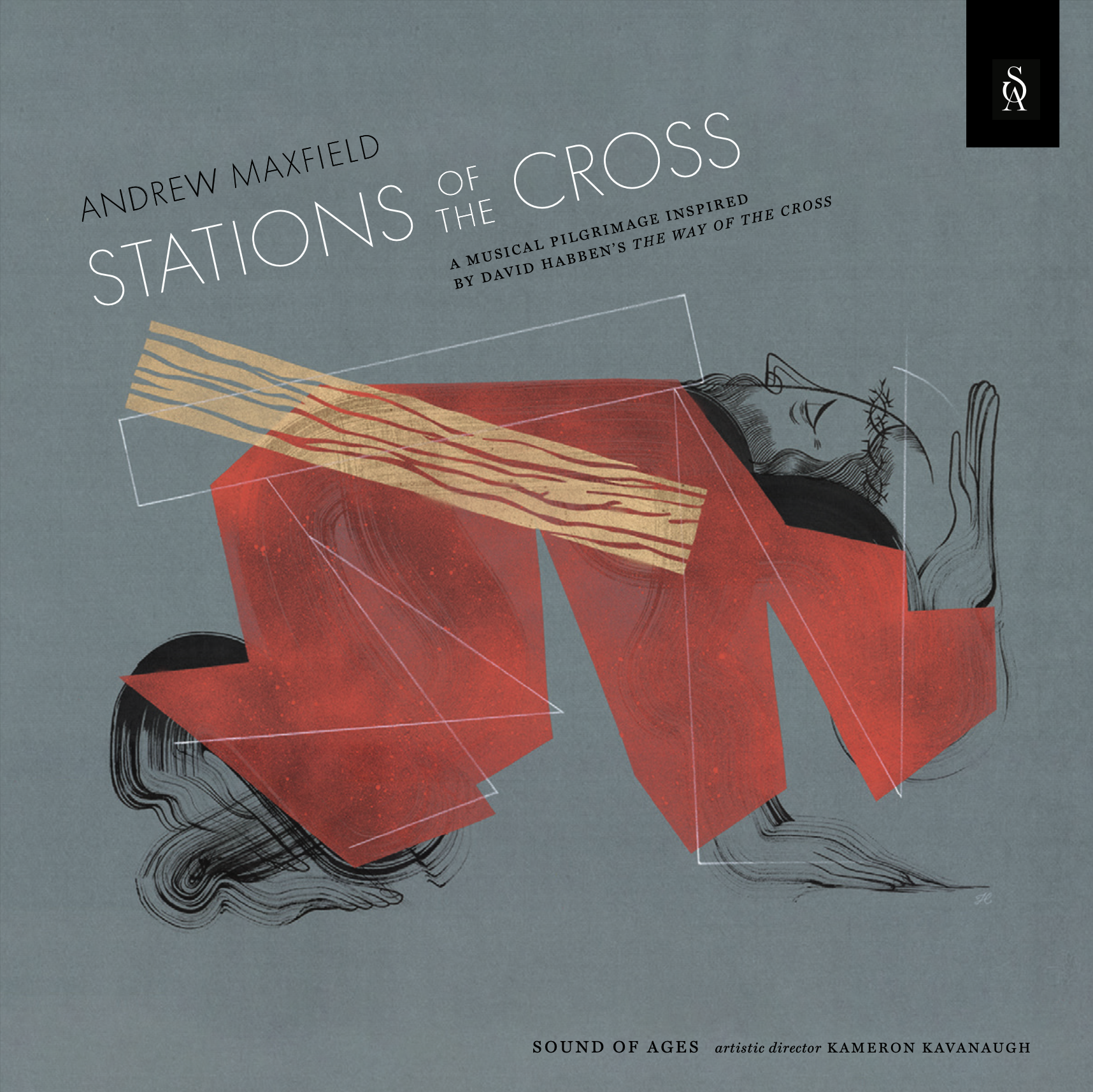

Stations of the Cross

Commissioned by the BYU Museum of Art, Sound of Ages will be premiering the latest Masterwork by composer-in-residence Andrew Maxfield. Inspired by The Way of the Cross, a series of drawings by artist David Habben that depicts the tradition Stations of the Cross native to the Catholic tradition. It is a musical pilgrimage approximately 60 min. in length. The piece will be premiered on March 27, 2026 (Good Friday) with a release on vinyl and streaming the same day.

Premiere Date

3.27.2026, BYU Museum of Art

Musical Forces

Soprano 1

Soprano 2

Alto

Tenor

Baritone

Bass

Electric Guitar

Sus. Cymbal

This is a non-ticketed event and seating will be available on a first come first serve basis. Reserve your seat through Sound of Ages invitation here:

Music on The Way: The Via Crucis and the Mechanics of Mystery

“However numerous are the mysteries and marvels […] discovered and […] understood in this earthly life, all the more is yet to be said and understood. There is much to fathom in Christ, for he is like an abundant mine with many recesses of treasures, so that however deep individuals may go they never reach the end or bottom, but rather in every recess find new veins with new riches everywhere.”

–St. John of the Cross (1542-1591)

In Catholicism, the word “mystery” holds significant meaning. It is defined as “a divinely revealed truth whose very possibility cannot be rationally conceived before it is revealed and, after revelation, whose inner essence cannot be fully understood by the finite mind.” As Pope Paul VI once described, they are “a reality imbued with the hidden presence of God.”

Mysteries occur at the intersection of tangible certainties and divine truths. Though incomprehensible, they are not unapproachable. They are meant to be entered—and re-entered. Because human experience with the Divine is mediated, there is a need to give form to mystery through liturgy, ritual, and structure. The Via Crucis (Way of the Cross or Stations of the Cross) is a prime example of this. Traditionally marking fourteen events along the road to Calvary, this devotion invites participants to not only collectively recall Christ’s Passion, but empathically walk with Jesus as he falls, suffers, and dies for their sakes. Prayerful prompts, pious gestures, sacred hymns, and visual iconography surround the practice, facilitating a fully immersive memorial for worshippers.

During Lent, the Stations of the Cross mediate the Paschal Mystery, a doctrinal term for the miraculous gift of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection. Believers participate, often more than once, in this commemorative pilgrimage in honor of Jesus’ final saving acts. Repetition is an inherent feature of this practice. Such repetition serves a didactic and meditative function, but it also reveals our impulse to return to things not yet fully understood. With each repetition of these devoted acts, believers enter in—if only a little further—into the mystery of Christ.

Visual representations of the Via Crucis can be found in every Catholic church. Although only activated by specific prayers and hymns reserved for the weeks preceding Easter, they are a constant witness of the Paschal Mystery and relate to virtually every other act of worship that takes place throughout the year. For centuries, artists around the world, known and unknown, have been commissioned by Catholic parishes to create compelling versions for their congregations—Giandomenico Tiepolo’s being one of the most notable.

The proliferation and standardization of this image series also attracted artists in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including Henri Matisse, Barnett Newman, Robert Wilson, and now David Habben—some of whom saw fit to add a fifteenth station.

Composers, too, have found themselves inspired by the Stations of the Cross and the Stabat Mater hymn that often accompanies them: Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Franz Liszt, Arvo Pärt, and Michael Hicks come to mind. Even the associated prayers—be they offered by clergy or self-guided by laity—have been reimagined, rewritten, and reinterpreted to inspire certain associations among supplicants.

Why then, when there are already countless visual examples and several musical adaptations, attempt another?

The Stations of the Cross, like most religious rituals, not only requires revisitation, but it also uniquely welcomes reinvention. The value, I believe, in returning to the Via Crucis as so many others have, lies in its continued thematic potency and ability to catalyze the mechanics of mystery. Mystery is entered through repetition and memory. Repetition is built into tradition: annually, textually, culturally. Memory is, to borrow one writer’s phrase, “its own thing each time it’s recalled.” As a regenerative ritual, each time the Way is walked—or written, or painted, or composed—it is reborn.

Andrew Maxfield’s Way of the Cross is indeed, as he puts it, an “appreciation” of the composers and artists that have come before, of the tradition itself. But it is more than that. It is a profound recollection. Collapsing time, listeners suddenly find themselves on a pilgrimage among a crowd of witnesses to the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Repeated petitions, scriptural references, and patristic accounts constitute the libretto for each station, culminating in the ultimate cliff hanger. As we follow the voices to the sepulcher, we too, encounter an empty tomb. It is the Paschal Mystery in musical form.

May listeners enter in.

Maddie Blonquist, Roy & Carol Christensen Curator of Religious Art

Brigham Young University Museum of Art